Influencer

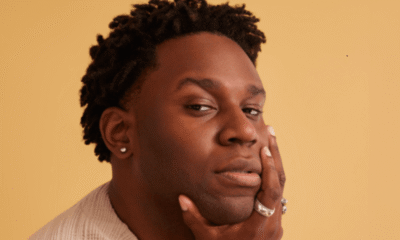

Nathan Kessel On Designing Virality At Scale Without Losing The Human Element

Nathan Kessel does not think about his audience in terms of millions. He thinks about them as people who might need a reason to laugh today, and that mindset has helped make him one of the most-watched creators in the world.

Nathan drives more than 750 million views each month across YouTube (11.2M subscribers), TikTok (10.8M followers), Instagram (2.5M followers), and Facebook (1.7M followers), with more than 1.2 billion views in the past 90 days alone. His videos range from tightly looped absurdist bits to animal-driven chaos, couple dynamics, and recurring formats engineered for repeatability. Yet behind the scale is a creator who remains resistant to milestone theater.

“I’ve never done, like, ‘Oh my gosh, thanks for a million,’ or ‘Thanks for 10 million,’” Nathan says. “Because to me, that kind of takes humanity away from every individual person that’s actually there.”

That philosophy underpins both his creative output and his business. Today, Nathan is the founder of The Virality Network, where he advises brands, platforms, and public figures – including YouTube, Disney, Pokémon, CeraVe, Activision, and Paramount – on how content actually spreads. His work sits at the intersection of instinct and systems, where emotional relatability matters as much as algorithmic fluency.

This balance, however, did not come from a traditional creator playbook. It came from a life that, by his own description, had to be rebuilt from scratch.

From Opera Prodigy to Reinvention

Long before he ever picked up a phone to film short-form video, Nathan was training for a very different stage. A former opera prodigy, he began singing professionally at 16 after joining the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s choir. He went on to train at the Eastman School of Music and Rice University, where he completed a Master of Music degree.

By his early twenties, Nathan had already sung with orchestras and opera companies across the U.S. and internationally. The path ahead was clear. Then, in 2009, everything changed.

Nathan survived a traumatic brain injury that left him with ongoing memory loss, migraines, and fatigue. He had to relearn how to walk, speak, and function. The injury also reshaped how he experiences emotion.

“I got hit on the right frontal lobe, and I got hit with the happy stick,” he says. “So, I feel a lot happier than most people.”

That outlook would later become central to his creative mission, but at the time his focus remained on music. He worked multiple jobs while studying, teaching SAT, ACT, and TOEFL (Scholastic Assessment Test, American College Testing and Test of English as a Foreign Language) prep, singing in professional choirs, giving lessons, and tutoring high school subjects. “I had about seven jobs while being a full-time graduate student,” he says.

Then, in March 2020, the pandemic shut everything down.

The Pandemic

Rice University reported its first COVID case early, forcing an immediate shutdown. Performances disappeared overnight. For the first time, Nathan felt deeply unmoored.

“I took those two days to just stare at the wall and be depressed,” he says. “And I finally was like, ‘If I’m depressed, the rest of the world must be in total and utter shambles.’”

That realization pushed him toward action. On March 3, 2020, Nathan downloaded TikTok and began posting, not with a growth strategy, but with a simple goal. “It’s my mission to make one person smile today,” he says. “That mission has never changed.”

One of his first viral moments came from an improvised challenge involving a stale marshmallow and a mug. “I said, ‘If this goes in, I’ll get a SpongeBob tattoo,’” he recalls. It went in. The tattoo followed.

“I never looked back,” he says.

Learning the Cost of Virality

Early success brought experimentation. Nathan tested formats aggressively, including a long-running prank-based narrative known as the “Karen” series, which featured escalating neighborhood antics. The videos performed at massive scale, often reaching tens of millions of views.

Then the platform rules shifted.

“TikTok started taking down all of those videos,” he says. “They called it bullying and harassment at that point.” What stung was not just the removals, but the cost. “I was spending six to ten hours a day prepping for those videos,” he says.

As distribution collapsed, so did the return on that effort. “That’s when I really started pivoting,” Nathan shares. He moved away from labor-heavy production toward formats that could be executed in seconds, not hours.

“How can I do something in seven seconds without setting it up for eight hours?” he recalls asking himself. “And really create an entire storyline in five to 14 seconds.”

That pivot marked the beginning of his current operating model.

Designing for Repeatability

Today, Nathan approaches content as a portfolio of repeatable systems. He openly refers to certain formats as tools he can deploy at will.

“I have my series that I know I can pull out of my pocket anytime,” he says. “If I’m sick, I’ll do ‘Balls of Fate.’ I throw ping-pong balls into the sink, and it’s 20 million views, 80 million views, at least a million every time.”

The goal is not novelty for its own sake. It is reliability. “I’m never going to spend time like that again on content creation,” he says, referring to earlier, more elaborate productions. “You don’t ever know the lifespan of a series.”

He credits that mindset for allowing him to sustain scale across platforms while preserving personal energy, a crucial consideration given his ongoing health challenges.

“I feel like I’m practically retired,” he says, half-joking. “Because I have a formula.”

Creativity as Emotional Engineering

Despite his focus on systems, Nathan does not see his work as mechanical. Creativity, he notes, has simply changed mediums.

“In opera, you train in Italian, German, and French for years to take people away from the stresses of their world and make them feel something,” he says. “Now, it’s about making somebody laugh.”

Ideas come from everywhere, Nathan shares. Some are born from dreams. “I’ll wake up laughing so hard from a dream that I start crying,” he says. Others come from real-life moments with his fiancée, Anna (@imthe_annag), or from the animals that populate his content universe.

“Creativity now comes from the environment around me,” he says. “It’s very spur-of-the-moment.”

That informality is intentional. “It’s not about me,” he says. “There’s no desire to have fame here. It is purely about making people feel something.”

Building in Public With Anna

Nathan’s relationship with Anna has become a core narrative thread in his content. Both were creators before they met, and they began collaborating organically early in their relationship.

“We started making content pretty quickly,” he says. “It was never stressful. If we ever get into an argument, we’re not going to film.”

The result is content that feels unforced, according to Nathan. “It’s just how we act,” he says. “We’re just having a blast.”

That reached a peak when Nathan shared his proposal to Anna. “Seeing how excited the world is to celebrate our love is surreal,” he says. “That’s probably my favorite moment I’ve ever had in this career.”

Virality as a Service Layer

Behind the scenes, Nathan has formalized what he’s learned. Through The Virality Network, he consults on strategy, format design, and platform mechanics, translating intuition into structure.

“There is a really specific formula that you can follow,” he says. “I want to help people actually go viral and take it to the masses in a synthesizable way.”

Unlike many creators who guard their insights, Nathan is explicit about metrics. “If you want a video to get 100 million views on YouTube, it’s got to be 16 to 24 seconds,” he says. “The retention rate has to be longer than the video.”

For TikTok, he is even more precise. “Don’t do anything less than 6.3 seconds,” he says. “If you keep it between 6.3 and 8.2 seconds, you start getting a 100 percent retention rate.”

He regularly lectures at universities including the University of Southern California, Loyola Marymount University, and California State University, Northridge, and sees education as part of his responsibility.

“I have nothing to hide,” he says. “Social media is the way of the future.”

Giving Back at Scale

More recently, Nathan has begun experimenting with philanthropy as content. One series involves responding to viewer requests for help, including sponsoring Christmas gifts for a single mother of four.

“My viewers have given me my life,” he says. “I want to give back to my viewers.”

For Nathan, this is not branding. It is reciprocity. “I consider my platforms like a TV network,” he says. “It’s going to be the most positive thing.”

His advice for aspiring creators is blunt: “Throw out all your plans. Pick up your camera, film something, and post it.”

Fear, he argues, is misplaced. “What’s the worst that can happen?” he asks. “You go viral. It changes your whole life for the better.”

What Remains

Strip away the views, the formats, and the systems, and Nathan returns to the same motivation that launched him in 2020.

“I hope that long after I’m gone, people can still look at it and just laugh,” he says. “There’s always a reason to laugh.”

For a creator who has engineered attention at a planetary scale, the goal remains profoundly small.

“One moment in their day,” he says, “where they feel human.”

Checkout Our Latest Podcast